This article was originally published at Coregamers on June 11th, 2008

Technology alone fails to explain the qualitative leap between MYST and RIVEN. The sumptuous, haunting and masterfully lit vistas of the sequel to the best-selling CD-ROM boasted such sophistication as to place them in a class of its own in 1997, and in the years that followed. While it is undeniable that the fidelity of renderware witnessed exponential progress during the interval that separated both releases, there was a palpable sense of artistry behind each of its many spellbinding locations that hinted at the presence of a strong authorship, vision and intention.

Richard vander Wende is a concept artist and matte painting designer with a long career in the fields of animation and film. He is generally recognized for his collaborations with Industrial Light and Magic in the production of the cult fantasy film WILLOW, as well as the world-renowned Disney animations ALLADIN and BEAUTY AND THE BEAST. A USC Art Center College of Design major, his first paid works included contributions to the laserdisc-based arcade games DRAGON’S LAIR and SPACE ACE, at Don Bluth’s.

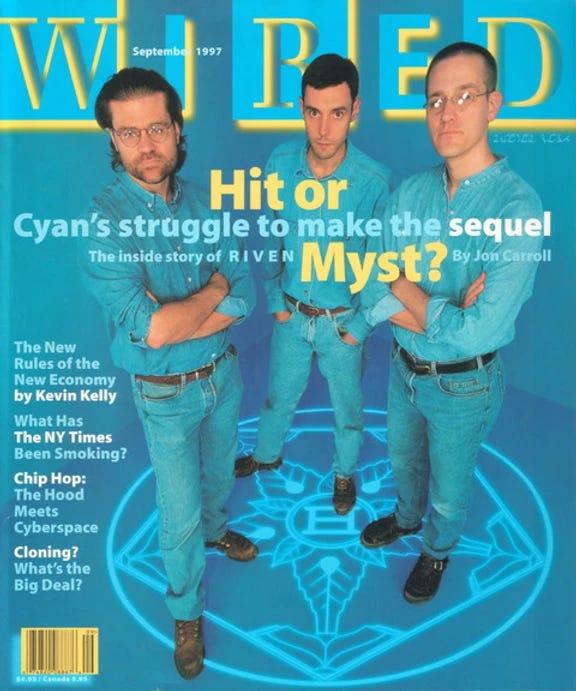

None could predict, however, that his talents would be placed on retainer by Cyan, the north-american studio founded by Robyn and Rand Miller that became one of the most recognizable references in the industry after the release of MYST - a game which, despite its complete lack of popular appeal, became a multi-million dollar sensation. Although the notion of integrating a third entity to their creative core was not initially contemplated, the fraternal duo extended vander Wende an invitation to form a trio; theirs a firm conviction that he alone could turn their intricate vision into being. More than this, we know today, he helped elevating it to new heights.

Aside from constituting a bold new chapter in the long history of graphical adventures, the publication of RIVEN signaled both the end of Cyan, as it once was, and the birth of Cyan Worlds; a change provoked by Robyn Miller and vander Wende’s decision to abandon the studio in pursuit of other aspirations. Recent sequels, integrating the latest advancements in pre-rendered graphics design, have struggled to maintain the high standard this game once set. While competent, none has triumphed in recapturing its delicate aesthetic refinement, foreignness or restraint. Technology alone could not.

COREGAMING : You had the pleasure of being a part of Cyan in the last years of its existence, when Robyn and Rand Miller created their last project as a team. In what circumstances did you make their acquaintance?

VANDER WENDE : We met at a software expo at the Los Angeles Convention Center in 1994. I had been given the ticket of a friend who was unable to attend. It was a disappointing little show and after just fifteen minutes or so I had seen it all and was ready to leave. I was on my way out when I noticed an intriguing area surrounded by dark curtains. Hoping there might be something there that would validate the gas I'd spent to get there I decided to have a look. Inside was a large, dark space, and around the perimeter were desktop computers displaying an array of current CD-ROM games. At the time I wasn't really interested in games but MYST was an exception - I had recently seen it at a friend's house and was very impressed. It didn't take me long to locate several stations where people were deeply immersed in the game. I lingered a few minutes watching them struggle then finally decided to leave.

As I retreated toward the exit I noticed someone else observing the players from the darkness beyond the glowing screens - someone that looked vaguely familiar. It was Robyn Miller, whom I'd recognized from the short 'making of' video they had included with the original release. I'm normally hesitant when it comes to conversing with strangers but such was my appreciation of MYST that I was determined to at least let him know what a great thing I thought they had achieved. We ended up talking for a couple hours that day (Rand joining us somewhere along the way), and two months later I was in a garage in Spokane, WA working on RIVEN.

CG : What qualities do you think the company was looking for when they hired you to create RIVEN?

VdW : I was told by Robyn that they weren't looking to hire anyone at the time that we met. Once we began to sketch out and build the first island, however, it soon became apparent that in order to achieve the level of quality and detail we desired - in the two years we had initially been given to complete the project (it ultimately ended up taking three and a half) - we were going to need help.

When it came to evaluating potential additions to the team, creativity and a person's sense of aesthetic were more important to us than technical proficiency or experience. Companies tend to put too much emphasis on proficiency with software, then seek to substantiate a prospective employee's claims by the number of bullets on their resume. But Robyn and I felt that anyone we might hire would be able to learn the software - our primary concern was the thinking and artistic dimension that might be brought to the project. Most of the people that ended up joining us had very little experience with 3D prior to coming to Cyan.

CG : Your visual concepts for the game were very organic, from unusually-shaped building structures resembling natural geological formations to the sporadic manifestation of a creature whose morphology hints at creative juxtapositions of known animal forms. In fact, these elements seem to be pervasive in your body of work as a whole.

VdW : Before the age of computers algorithms were called artists. The real world to me is the strangest and most wonderful place in all the universes, real or imagined. I have never seen an artist's orchestration of color, for instance (to consider just one aspect of our world), that could match, let alone exceed, the beauty and complexity that exists in nature. The process of creating believable fictions, then, is a matter of successfully analyzing and synthesizing the world we live in.

But there is more to designing good fictions than that. Beyond the aforementioned effort to simulate the rules of reality there are a couple other qualities I frequently strive for --

One is to try to strike a balance between strangeness and familiarity. Familiarity provides a common link to things - a way to connect with them. And strangeness creates a sense of mystery that impels you to know more about the object in question. For me, maximal interest in a design is achieved at some point between those two extremes. If something looks too familiar people tend to file it away without much consideration. If, at the other extreme, your design is utterly and completely alien there will be no way to relate to it. There may be the odd instance where that's exactly what you need, but for the most part you want people to be able to relate to your designs, even if only slightly. For me, again, it's a matter of finding an appropriate balance between those two attributes.

The other quality I strive for in my designs is a metaphoric dimension - to imbue them with features that suggest things beyond what you get from the initial read. Sometimes the change of a color, or the alteration of a single line will suddenly call to mind something else from your experience that fits with or enhances what you're trying to say. Designs that are rich in this regard will resonate with many such instances.

CG : Concerning the architectural components found in the game, I understand you borrowed many an element from Middle-Eastern architecture? It was, after all, a source of inspiration that had suited you well in your previous work for ALLADIN. Golden domes, however different in shape and purpose, thus came to find their existence in both these universes.

VdW : One of the great things about designing for film, or games like RIVEN, is the visual research you get to do. In the case of ALLADIN I investigated the historic and traditional architecture of the Middle East - which was fascinating. It's possible there may have been some residual influence once I moved to Cyan but I think the bold architectural forms we came up with for RIVEN were mainly the result of a story consideration: that all of the non-native structures you see were designed by one man (Gehn) - a man with an overly pragmatic personality and very limited resources. I think our intention with RIVEN was (…) more akin to creating new branches on the evolutionary tree of existing forms. Our sensibility was much more Postmodern - our building blocks were the detritus of history. And the odd juxtapositions, while deliberate, were more the result of our design goals (as stated before) and a constant, rigorous consideration of the overarching story.

CG : So much time has passed since the project was in development. What does RIVEN represent to you?

VdW : Ten years after its completion RIVEN remains the most satisfying work experience I've had. Film and game production are highly collaborative endeavors so it's a rare privilege to be able to have such a comprehensive influence - especially on such a high-profile project. Were it not for Rand and Robyn I never would have had that opportunity. As gratifying as it was, though, the most valuable thing I gained from that experience are the friendships I formed along the way.