This article was originally posted at Coregamers on August 28th, 2008

I. HOPE

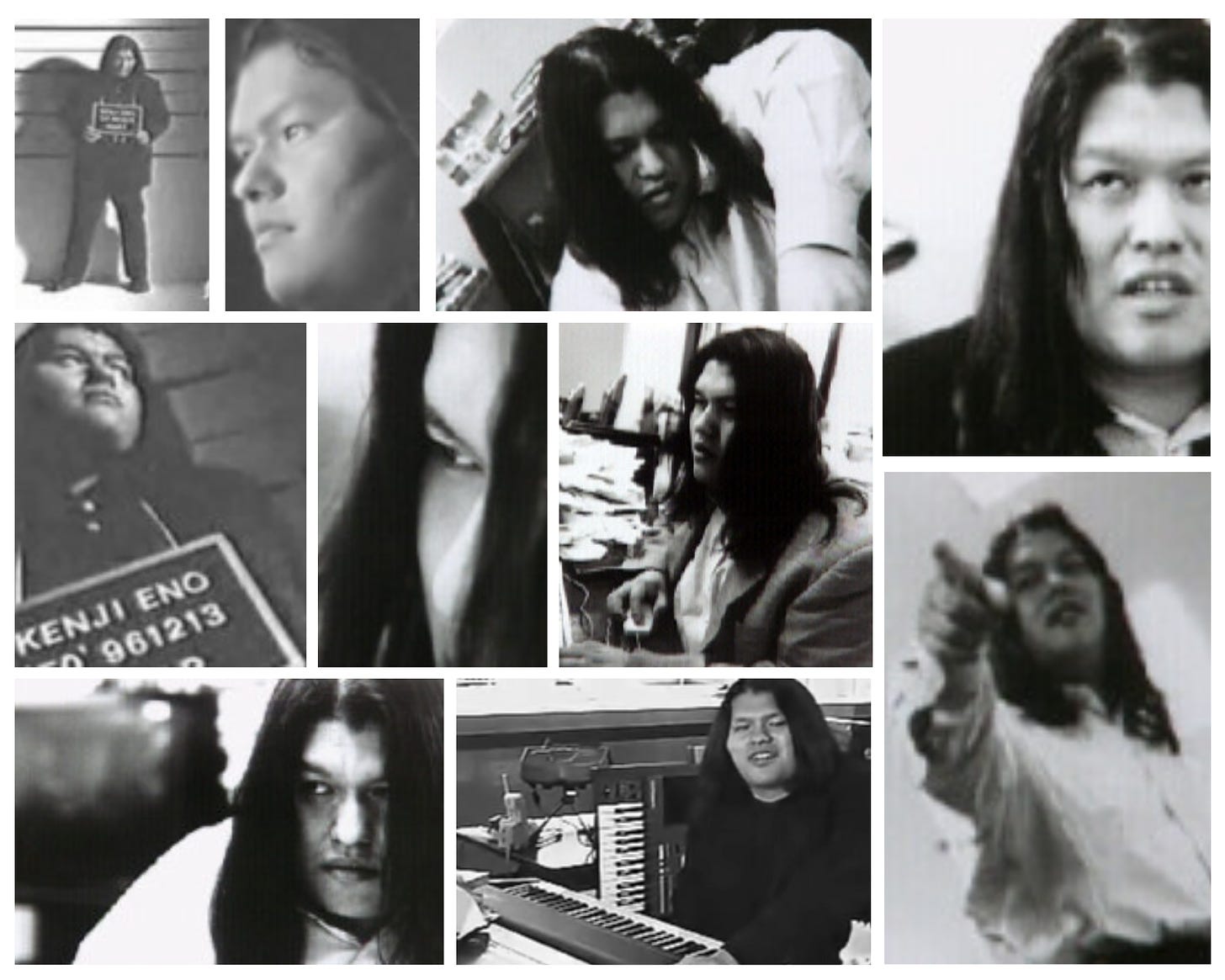

Despite a prolonged absence from the limelight, the myth of Kenji Eno has only strengthened in recent years. His creations as an independent and multifaceted designer have acquired a cult status among knowledgeable Japanese and western game players who appreciate his irreverence and non-conformism. This enduring prominence and admiration from both followers and peers, however, came at the cost of years of strenuous and unaided labor.

Shortly after turning seventeen, Eno dropped out of high-school, a radical decision which irreparably stained his reputation in the eyes of gossiping neighbors. For a time, he allowed himself to live a carefree life, travelling in the pursuit of new places unlike that in which he had grown up. He felt fascinated by the strangeness of strangers, each individual representing the potential of a life-altering experience and cultural enrichment. It wouldn’t be long until he came to terms with the harsher aspects of reality. Forced to contemplate his future and make concessions, he set out to find his first job in the highly competitive and conservative Japanese labor market of the late 1980s.

After several failed attempts to find a stable and sustainable activity, Eno stumbled upon a pathway to the lower sectors of video game production. Sensing the dangerous allure of arcade parlors as a child, video games seemed to him a promising perspective and a match for his peculiar personality. Unable to afford a synthesizer, the young YMO devotee taught himself to use his computer as a musical production tool. It was this knowledge that earned him his first prize in an amateur video game creators contest. This trophy was the crowbar with which he forced his way into digital game production at a professional level, scoring a decently paid job at a minuscule studio going by the name Interlink. There, he sharpened his skills further and became acquainted with the kind of recent software tools that was verboten to mere amateurs.

In 1989, he had scraped up just enough to establish his first independent studio: EIM, or Entertainment Imagination and Magnificence. It would be Eno’s escape plan from his Interlink which, by that time, had expanded into a larger and less personal collective. While the idea of creating an autonomous new company was a confirmed step-up, enabling him to produce better and more functional games for the Famicom, he later regarded this as one of the most straining and unpleasant moments of his professional career.

At the time, best practices dictated that games needed to be created around popular characters, a way to mitigate risks by capitalizing on known quantities. In addition to the supported production expenses for the game program and the manufacture of cartridges, the publishing a game on a Nintendo system equally required strict adherence to software protection codes - an artful clause demanding additional investment in return for their famed seal of guarantee. Such obstinate impositions created in Eno a feeling of distress and irritation that eventually led him to shut down EIM, having produced ten games in total between the years 1991 and 1993.

II. ECLIPSE

Fatigued by the three year period spearheading his own startup company, Eno took a sabbatical from the video game industry to become a collaborator in an automobile magazine, where he nevertheless kept in touch with the latest developments in digital technology. In his visits to the United States, he learned about the new trends flourishing inside the world of electronics and software companies. The so-called cool and relaxed approach to business struck him as the eminently desirable departure from rigid and severe nature of Japanese business.

By the time Eno met Trip Hawkins, he was already looking to set up a new Japanese branch for his new and resourceful 3DO company. Hawkins was also receptive to the projects and ideas pitched to him by Eno, seeing them as the oriental flavoring powder his system’s paltry and bland software library desperately needed. These corporate values and partnerships formed on the other side of the world inspired him to establish WARP, a studio specializing in the developing games for the ephemeral 3DO. The new console was based on the CD-ROM format, an inexpensive technology that allowed smaller companies to release their products to a larger audience, free from the steep cost of cartridge production. For Eno, this was the long sought panacea to all ailments suffered in past dealings with Yamauchi’s middle management.

While the European and North-American markets would only learn about WARP in latter half of the ‘90s via the game D, the Japanese market was more than one year ahead with games like TOTSUGEKI KARAKURI MEGADESU!!, a singular first person fighting game; and the similarly bizarre puzzle game FLOPON WORLD, alternatively known for its pun intended title TRIP'D. In addition, Japanese players were exclusively greeted with other exclusive launches such as OYAJI HUNTER MAHJONG (1995) or SHORT WARP (1996), a visionary celebration of the WARP's ideals and aesthetics by way of multiple mini-games.

D - or D'S DINNER TABLE as some early press had called it - was the work that consecrated Eno as an author capable of exploring an interactive drama using the potential of pre-rendered graphics and animations. In a daring attempt to disrupt the customary practice of filming real actors against a blue screen, WARP gave birth to Laura, one of the first virtual actresses to star in a video game. Attempting to convey complex emotions, the synthespian’s facial elements were made possible by a highly malleable, rigged model that could be fine tuned to exhibit a host of different expressions.

Even its mechanics were very much inspired by the graphical adventures of old, D was an attempt to take a familiar genre and elevate it with the most recent technology. Remarkably, the narrative of Laura's search of her mass-murdering father was only inserted into the game after the project was already well under way; something which could account for the unusual storytelling method, primarily consisting of flashbacks to defining moments of her childhood. A thrilling cinematic experience, D was one of the first console games to present such a mature theme, with a foreboding atmosphere and complex characters whose acts were defined by non-linear motivations.

By 1996, the studio’s aspirations to produce the ultimate interactive movie led to the release of ENEMY ZERO, a space adventure that pays direct homage to renowned science fiction cinema and literature classics. Marking the second appearance of the vactress Laura, the Saturn game blended CGI graphics with sporadic, polygon-based 3D combat sequences that represent a major departure from what had been seen in their previous work. Trapped in the Aki space station, the player must face the threat of an alien species that exists invisible to the human eye. These creatures, classified as E0, can only be traced using a weapon that emits different tones that inform of their position or proximity. A formidable achievement in visual excellence, ENEMY ZERO merits additional recognition for its original integration of sound design in its core interactive element. Another notable aspect associated with the it relates to how Eno pursued and persuaded the illustrious composer and pianist Michael Nyman to compose his first and last video game soundtrack.

Not long after the release of D, Eno experienced an event which increased his awareness of the world of sounds around him. The 1997 Saturn game REAL SOUND: KAZE NO REGRET - meaning the Wind's Regret - originated from his encounter with a group visually-impaired game enthusiasts. Observing the methods they employed to work around their disability and play games not suited for their condition, Eno felt the urge to write and produce an interactive story that could be enjoyed by this often neglected group. Moreover, he convinced SEGA to pledge hundreds of consoles to related institutions as part of the terms for the release deal. The degree of detail and attention paid to ensure REAL SOUND could be enjoyed despite this disability was such that even printed materials included were fastidiously translated to Braille.

All through its four CD narrative of a love story set in Tokyo, REAL SOUND tapped into the seldom used potential of games as medium for inclusiveness. By rejecting a number of preconceptions of what makes a game appealing, or how it should function, this title also proved to be essential in the establishment of WARP's identity as an autonomous company moved by its own, unique objectives.

In a second attempt to enter the console market, the 3DO company developed a 32-Bit console named M2, of impressive technical specifications, later sold to the Japanese company Matsushita - vulgarly know as Panasonic. Several titles, including works from Konami, were already in the later phases of development by the time the Japanese electronics giant changed plans and halted its release. A possible motive related to the impenetrability of the market, at a time when Sony was surpassing even the most optimistic sales projections for their PlayStation, while SEGA was still in the race with its Saturn, and Nintendo was in the process of going global with their highly anticipated 64-Bit architecture system.

Among the titles planned for the launch of Panasonic M2 was D-2, an unusual sequel to the original 1995 WARP classic. The images and videos recently recovered by game historians and archivists show the studio was working on a full 3D game, seemingly in alpha phase, with some impressive lighting effects and distinct presentation. Some argue that the game was a direct sequel to D, with Laura’s son as the main character trapped in an opulent manor haunted by otherworldly entities.

With the advent of the new 128-Bit console’s release in the Japanese market, the SEGA Dreamcast, Eno recaptured the experience of REAL SOUND: KAZE NO REGRET in a whole new release of the game. Apart from the "classic mode", previously used in the Saturn version, the studio added a whole new "visual mode", including images and photos captured by Eno himself. This original sound drama, released in the same year as the console, also came to be known for a small extra that was included within the game box named D-2 SHOCK!, a unique GD-ROM preview of the upcoming WARP release.

As a result of the good professional relationship between with SEGA and WARP, Eno found a way to breath new life into the aforementioned D-2 project, having decided to redesign the game from square one and launch an alternative version for the Dreamcast, released in 2000. Laura, which seemed to have but a supporting role in the original project for the M2, assumed once again the lead in this ecological thriller set in the snowy Canadian wilderness. Like its stillborn twin, D2 resulted from the ambition to produce a three-dimensional game space wherein CGI was employed exclusively for added visual detail in the form of cut-scenes.

D-2 was launched in Japan and later in the US, uniting several game genres in one: action, adventure and RPG elements. Surprisingly, the interior spaces were explored in a subjective perspective, evoking with great accuracy the genre and game play previously explored in the first D title – such was the detail of the 3D engine created by this team. The high-production values, puzzling narrative and matchless ambiance, along with Eno's exquisite music score, resulted in one of the best horror and paranormal-themed video game experiences to ever appear on a console.

After more than five years as an active studio, all these efforts failed to ensure sufficient financial return for the group to remain active in the industry, forcing Eno to broaden WARP’s market scope. For a period, the renewed SUPER WARP engaged with other media contents such as DVD, networking or online music, until it finally faded away, never again to produce or release a video game.

As a self-reliant creative force, WARP enunciated a new paragraph in the chapter of Japanese independent video game market, branded by the irreverence of its multifaceted founder and leader. The perceived value of the studio’s body of work continues to increase as internet repositories of digital obscurities make them known to a more mature and discerning audience, enraptured by the prospect of their discovery.

III. BLISS

INTERVIEW WITH KENJI ENO

After eight years since his last Dreamcast title, Eno returns at last with the announcement of a new project. A precious example of his recent work can already be seen in the game NEWTONICA, to which he contributed with abstract visual concepts and a suggestive background music theme.

Avoiding the subject of his new game on purpose, out of respect for the author's vow of silence, I tried to make this an easy going, informal interview that plays like a dialogue, covering other subjects than those already featured elsewhere. I deliberately kept his answers as intact as I could so that the reader, too, could understand a little more about Eno’s mind.

COREGAMERS : The other day I was exchanging some emails with (your friend) Kenichi Nishi, whose independent projects, much like the greater part of your work, are impossible for a non-Japanese speaking player to understand due to the language barrier. Given this situation, did you ever think about the fact that European players were constantly being left behind?

Kenji Eno : Yes and no. For example, Warp's 1st major title, D, has 4 languages: Japanese, English, French and German. Despite being only four languages, that was heavy to me, because I can't understand French and German - almost nothing. But I had to check them, not only texts, but the voices too.I know more and many languages in the world. I think that I want my games to be played by as many people as possible. I remember when I was young, I watched French movies in my video player. Because there were no subtitles, I felt sad. I think I have to ponder on this problem, thanks.

CG : One can clearly understand from your position in life and in the world of game design that you are a non-conformist: as a unique means of communication, what do you think video games have to offer that no other medium can deliver?

KE : Interactivity.

CG : You were one of the pioneer game designers for 3DO in Japan, a country where there was little room for another console among the Nintendo-dominated market. In the opinion of some video game researchers and specialists, the 3DO system isn't just a colossal market failure: it is the most sacred example of Hawkin's visionary intention to unify the video game market, with only one system being produced by different manufacturers. One of the 3DO hardware creators, RJ Mical, once said that the project seemed like "almost an utopian Socialist idea". What are your thoughts on the subject of a universal game system as an abstract idea, as well as in the light of modern day 'console wars'?

KE : Like you said, (the) 3DO (company) had a good vision. That's one of the reasons why I created the games for 3DO. I love Trip Hawkins, he’s now on Digital Chocolate. I wish to see him again soon. But about “console wars”, I think it is difficult to understand and I think it’s much like ‘Star Wars’ – because this movie has more than just one director. There are various platform companies, different game players and many people in this industry. This “war” helped to make and still originates good consoles, you know. Consumers are entitled to make a decision and cast their vote by way of their purchasing preferences.

CG : I assume that as an experienced game designer, you must also play a great deal of games not only as a learning process, but for the pleasure of the experience. But since you're a renowned creator, you must have a very different perspective on the games that you play in comparison to the average game player. From a personal and professional standpoint, which were the games that you played so far that best display video game excellence and why?

KE : First of all, I am a video game creator. (Yet) I am a video game player when I play the game. I may have different perspective on the games, but every player has one, I think.

Some game creators think about game design while they play the game, But I don't. I just play. I just enjoy. About the games I played so far that best display video game excellence… many games. I can give you the three titles that made me a video game creator:

SPACE INVADERS / Taito / Arcade

First big impact of video game to me. I was addicted to it. I felt some kind of new culture appear.

PACMAN / Namco / Arcade

First video game, I felt the "art". Like "pop art". Visual, sound and program. So beautiful.

TRANSYLVANIA / PolarWare / PC

First video game, I felt like I was there. I really enjoyed being a part of an adventure. If I didn't play Transylvania, I couldn't have created D.

CG : You named two of the first and best examples of video game in the form of arcades (Invaderu and PakuMan). But, as we know today, this sort of entertainment is becoming secondary as people around the world prefer to meet up in virtual reality through online gaming than to actually go out and meet in the arcade parlor, play head to head. How do you feel about the decay of the Arcade gaming age?

KE : I loved the experience of playing arcade games. But that was a long, long time ago when I was 9 or 10. I used to play the arcade games in the dark rooms in Japan. So dark. A little Dangerous. There's many adults, and only a few kids like me. Smoke.

Drink, Drank. Chat. The sounds from game machines. That's the culture I loved. Online games? - too different for my taste.

CG : One of the fondest memories I have from your WARP games, like D and ENEMY ZERO, was that you always emphasized the creators behind the program. Instead of a boring credits roll, these games had a slideshow of the names with pictures and music. As you may have realized, that initiative was very important to players like me, who had always wanted to know a little more about what happens backstage. To what extent do you think is important for authors to come out and make a claim over their work, much like musicians or filmmakers take credit for their albums and movies?

KE : When I was creating first major title D, neither I nor and WARP were famous. Nobody knew me. If I had no success, I had to close. D was my first and last game where I was like gambling while creating.

But there was no famous character. It was not a sequel, and not a conversion title. There was not much money to do marketing. There were no ways for me to make game players aware unless I said something (about me) in the games. After CD ROM became dominant media, instead of cartridge (cassette) ROM, there’s a new “world” and more stories growing within video games: these worlds are what the creators deliver. I think it's the good way to understand what creators want before playing.

CG : Game creation is a daily process of team work. But you seem to have, on more than one occasion, played different roles in the production of your games, from game planning to musical score creation.

KE : Every time I do what I can do. That's all.

For example, for ENEMY ZERO, I ordered Michael Nyman to compose the music. Because I felt he's the best musician for what I was looking for in ENEMY ZERO. In REAL SOUND, I asked Keiichi Suzuki, who had created the soundtrack for the game MOTHER (EARTHBOUND), to compose and Yuji Sakamoto to write the script. I am a producer. I ask myself to perform a certain work if I’m the best person to make that part of the game.

CG : Looking back at your career so far, I understand you always regarded your job more like an artist with a personality than an engineer fascinated by numbers and code. Also, your creative power felt less restricted when you were able to found your own studio and realize your subjective vision. With those games you created autonomously, free from corporate restrictions and pressures, what do you think you have accomplished - and what do you still hope to accomplish with your future projects?

KE : I want to see how far I can go with video games - just that. Because after 2000, I did may works outside video games: planning, Graphic Design, Compose, Consulting, Branding, Concept Design and Marketing. I did this for many Clients. I had many experiences. And I have two children now. I've aged. Some of me has changed. Some of me is the same. I want to see what I can do with video games now. Don’t you?

CG : Indeed I do! So, the big news everywhere is that Kenji Eno is returning to the game scene (!) after many years. Instead of asking you about your new project, I would like to know what did you miss the most during your absence: what is that moment in the process of designing and publishing a new that makes you feel alive and rewarded?

KE : I feel I am happy that I can create the video game now and again. The greatest reward is to be able to make the game with a good companion. I really thank my friends and my wife. When my son plays my new game in near future, I’ll feel I am alive.

CG : What alternative themes would you like to see the industry explore haven't been so far?

KE : Any style is OK. But I want to play something new. And I want to play a game where I can feel the creators.

CG : The logotype for WARP (I always found it brilliant, like a sign of great things to come in a game). Who designed this logo and does it have a specific meaning?

KE : Me and designer "Miyazaki" at WARP made it. Its meaning is very simple! You see the logo of WARP. There's four screens on four TVs. It's after TV, like a four-frame comic.

W : End of TV broadcast. There's the color-bar.

A : After the color-bar, sand noise.

R: Oh, I play a game... it's an old type of game.

P: Bored! Power off.

CG : I guess everyone asks you about this: In the magazines of the time, D-2 was shown as an M2 project before there was even talk about Dreamcast. I still have the magazines that show the stills from the game. I recall a garden, a character in a silver armor, a bearded man. Those were amazing looking graphics and environments. What sort of game was D-2 (story, characters and the message of the game)?

KE : D-2 for M2 was like an action adventure game. Like Zelda. I don't wish to reminisce about the story because there's no D-2 for M2. No one can play, even me. That’s sad.

CG : My first contact, like so many other players, with D-2 was through the D-2 Shock disk. For the first time I was able to try the game. But what I recall the most about it was the sound test – the music was so calm and distressing at the same time. What sort of feelings do you like to convey when creating music? Besides producing, do you actually play any instruments?

KE : When I compose and create the music for games, I hope the music I compose will become "good BGM" (back ground music) Not just a song. I often play the piano, keyboards. I played brass instrument when I was young, at a brass band and an orchestra.

CG : Going through your projects so far, I don't think you've ever explored the handheld market properly. What is your position on the concept of handheld consoles - do you not find it interesting?

KE : Too small a screen for my taste!

CG : Finally, tell me a little bit about your life nowadays. It's got to be exciting, resuming your work as a game designer. What sort of reaction would you like to have this time from the public this time? You also mentioned your kids before: are they old enough to play? Have they tried to play any of your games?

KE : Any reactions, please. To have no reaction is the saddest outcome. My older son is 10 years old. He is able to play now. This is the first time he will be able to play one of my games. I hope he is able to understand that I am the designer.