Established in 1974, the Shibuya-based group Shirogumi was formed by ex-Toei Animation studio members and worked for the better part of its existence in the field of animated pictures. For the last fifteen years, the company managed by Tatsuo Shimamura turned to the area of special visual effects and computer graphics, actively participating in the creation of celebrated Japanese TV series and movies such as Returner, Always Sanchōme no Yūhior the award-winning anime Piano No Mori.

Their collaborations in the field of videogame development has equally played a large role in the group’s growth and expansion. They are among the most sought-after experts not only for the production of top-tier, pre-rendered movie sequences; but also for artwork design and in-game assets ranging from character models, props, lighting and animation. Over the last decade, they have been able to satisfy the demands of Japan’s elite software houses including Namco, Capcom or Square-Enix; all the while remaining accessible to small-scale independent ensembles as is the case of Grasshopper and Punchline.

Shirogumi has earned a unyielding reputation as one of the most reliable and proficient content creator in their category, accounting for ever increasing demand. Apart from the projects where the Tokyo group played a central role in the development course, the employment of specialists from this provenance for purposes of support and consulting has been similarly frequent. In this advantageous environment, suscpetible to exponential growth, names like Akira Iwamoto and Takashi Yamazaki from the Shirogumi workforce soon became a reference in CGI film direction.

Due to significant advancements in real-time rendering, provided by recent console and home computer technologies, the use of full motion video is slowly being supplanted by in-game full motion animation. As it has been often stated, the use of CGI has been a valuable resource for developers in achieving a greater level of visual detail that has been, so far, impossible to attain with real-time imagery. To a certain extent, some companies, mainly Japanese ones, continue to rely on pre-rendered graphic sequences as an enhancement to the intended visual spectacle - a feature so closely associated to the JRPG of the compact disc era –, seen as proprietary game engines remain incapable of rivalling the visual fidelity or the intricate lighting of FMV. In addition, the recurrent use of this technique as an embellishment has mutated into the form of a traditional resource, now deeply rooted in Japanese game design mannerisms.

This conundrum of pre-rendered versus real-time finds a not too dissimilar parallel in the motion picture industry, namely with the converse process of its piecemeal replacement of mechanical special effects, now constituting the most economic and flexible option for Hollywood filmmakers. In videogames, CGI has played the ungrateful role of the two-edged sword for long: at once providing exciting cinematics with otherwise unattainable degrees of detail, yet simultaneously generating acutely unpleasant contrasts among different strata of minutiae in the overall presentation.

With time, this implicit transition between the disproportioned parts became an impulse instantly assimilated by players the same as the now pervasive shifts between interactive and non-interactive segments of a game experience. High-resolution visuals ornate with state-of-the-art post-processing inevitably deprecate the raw character of comparably unpersuasive real-time geometries permitted by hardware generations, past and present. Such clearly identifiable unevenness, notwithstanding, should be forgiven in view of the technological nature of the contending schemes.

In all fairness, both have evolved towards the realization of a common objective as demonstrated by the visible similtudes shared by today's real-time 3D and the pre-rendered images of old. In this regard, CGI has served the laudable purpose of setting the technical and aesthetic standard for in-game visuals to follow. The very images that so delight the eyes of today will assuredly be surpassed by the real-time graphics of the coming years. Far murkier is the future of CGI itself.

Given the exception of several relevant titles where Shirogumi’s participation was less noticeable, the following list comprises the studio’s finest specimens of their talent in both traditional animation and three-dimensional rendering, adorning some of the most important titles of recent memory. Surprisingly, the range of the group's work is pervasive to the point of seeming ubiquity. If one is to probe their mind for the most memorable videogame introduction sequences of the last decade, a large portion are likely to bear the company’s seal of excellence. As questionable as the (abusive) use of this technique might be in the creation of videogames, and despite the improved transitions between modes as can already be witnessed in Mistwalker’s THE LOST ODYSSEY, there remains no plausible argument to refute the intrinsic optical spectacle casted in these memorable segments of digital graphics, whose individual merit is far beyond sane reproach.

FINAL FANTASY VII

Squaresoft 1997

TALES OF DESTINY

Wolfteam / NAMCO 1997

XENOGEARS

Squaresoft 1998

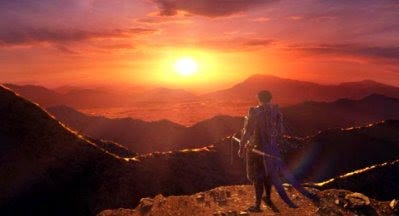

ONIMUSHA: WARLORDS, ONIMUSHA 2 & ONIMUSHA 3

CAPCOM 2001, 2002, 2004

RESIDENT EVIL ZERO

CAPCOM 2002

CLOCK TOWER 3

Human 2003

BATEN KAITOS: ETERNAL WINGS

NAMCO 2003

GENJI: DAWN OF THE SAMURAI & GENJI 2: DAYS OF THE BLADE

Game Republic 2005, 2006

SOUL CALIBUR 3

NAMCO 2005

DIRGE OF CERBERUS: FINAL FANTASY VII

Square-Enix 2006

RULE OF ROSE (see intro video)

Punchline 2006

SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI: DEVIL SUMMONER

Atlus 2006

VALKYRIE PROFILE 2 SILMERIA

Tri-Ace 2006

BLUE DRAGON

Mistwalker 2006

FOLKLORE

Game Republic 2007

EYE OF JUDGEMENT

Japan Studio 2007

LOST ODYSSEY

Mistwalker 2007

NO MORE HEROES

Grasshopper Manufacture 2007

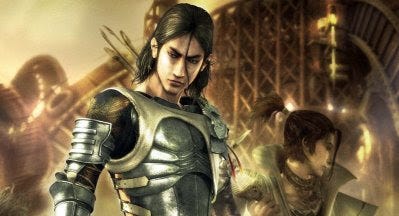

INFINITE UNDISCOVERY

Tri-Ace 2008

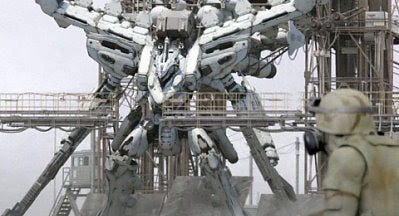

ARMORED CORE: FOR ANSWER

From Software 2008