Below is an assortment of texts written for social media over the course of a few weeks in the year 2020, part of my engagement with an ongoing initiative to produce a list of one’s prized video games. In view of my complete aversion to lists, I took the liberty to modify the rules and instead decided to ponder on the subject from the perspective of which games caused the most enduring impression in me and summon the words to communicate the reason why. In pursuing this exercise, I was able to narrow my choice to twelve game experiences which I snarkily dubbed games for life.

I.

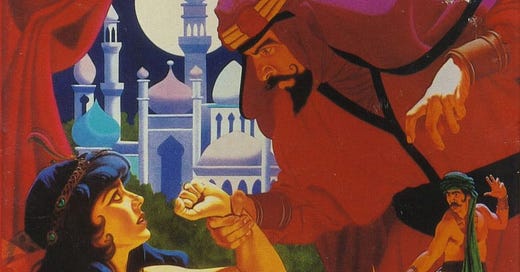

Prince of Persia

Jordan Mechner

Brøderbund, 1989

The first I saw this game, it was running on the monochrome screen of an 80386 PC at the local court office. At the time I had no objections to public employees using government-paid time and resources for purposes of leisure. I was only too keen on taking my turn at the table and leave my fingers to bask in the haptic charms of the mechanical keyboard.

A terse overture rolled out the plot swiftly like a silk carpet. The perfectly animated white sprite was brimming with spirit as it stood out against an inky backcloth. Sound output was but punctual and a five second-long ticktock afore respawn sufficed to instil urgency. The colour of bubbles fizzing from potion vials tipped the wink as to their consequence – those I failed to distinguish in my first admission into the dungeon.

All at once, a fleeting shimmer assailed the pervading darkness, blazed my eyes as the prince’s graceful contour stooped so as to lift a cast-off sword from the limestone floor. Now we stood a chance, it and I. The deep-seated tension when rushing towards a seemingly impossible jump; the sense of wonder navigating its maze-like stages – each new one at once more taxing and ornate – conveyed the notion that someone, somewhere, was at pains to elevate the sensory gamut of the medium.

PRINCE OF PERSIA was a leap forward. More than that, it was a leap through the mirror, an awakening. Unlike ever before, the wide-eyed infant that I was realized the existence of a mind behind the program; a remarkable one subduing all superfluous elements towards a potent essence that would elicit the most laudable creations - to this very day.

II.

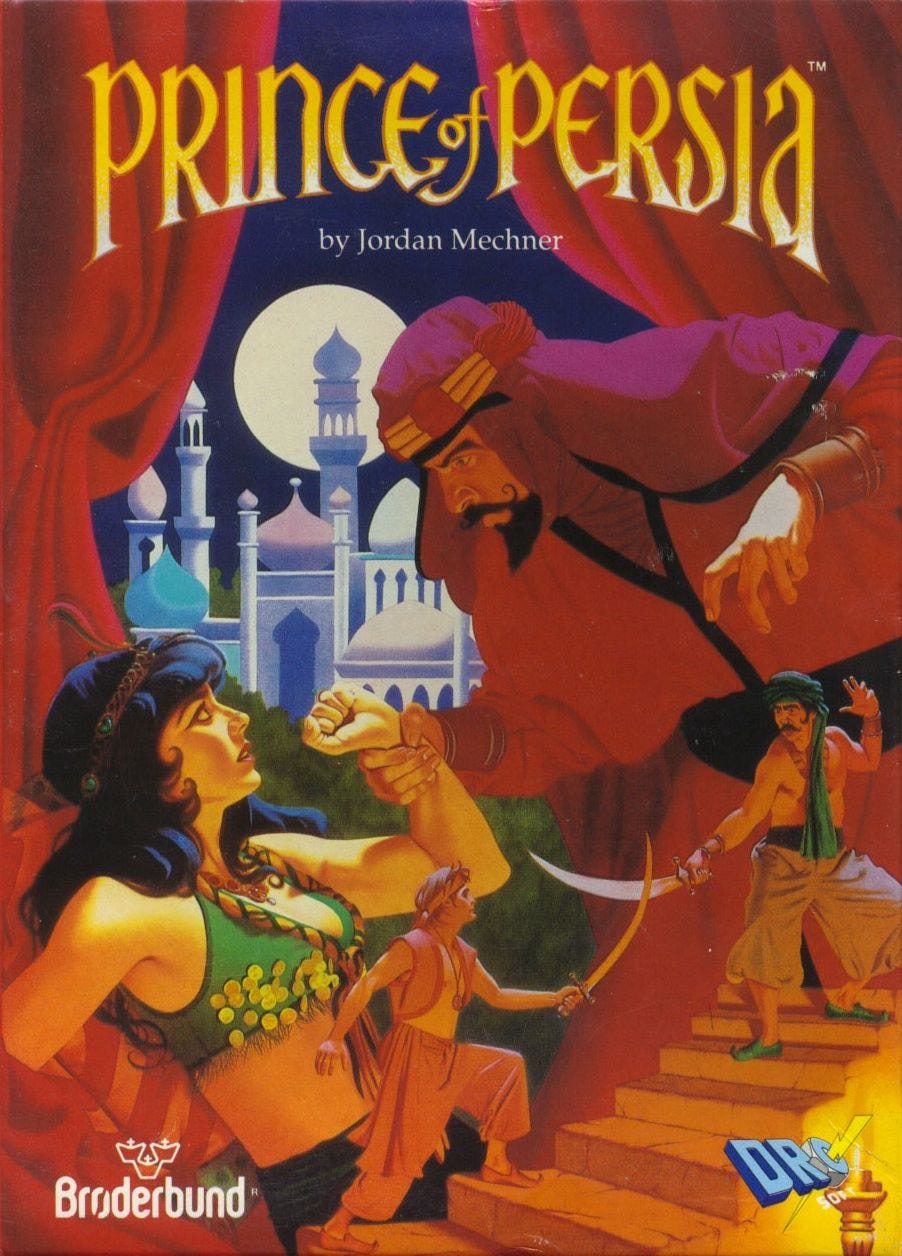

GADGET: INVENTION, TRAVEL, & ADVENTURE

Haruhiko Shono

Synergy, Inc., 1993

It was rather fitting that GADGET received the majority of its laurels from unspecialised media. Its moderate prominence at the time of its release is best understood within the context of computer and video game history. For all its countless debacles, the domestic prevalence of the CD-ROM was the all-important stepping stone prompting video games into what could be considered, broadly, as a third, higher stage of their existence.

The introduction of such a brave new framework proved to be highly enticing for a variety of authors – designers, inventors and creators at large – who found their port of call in a flourishing new segment of the industry where the lines between “interaction”, “communication” and “play” grew increasingly dimmer.

As the present decade nears its end, it is virtually irrelevant to determine whether GADGET – and, with it, a variety of titles in parallel alignment within this wavelength – consist of video games or otherwise. There, my contention has always been that it should, strictly for the benefit of the medium. The deafening quarrel of a generation was soundlessly overcome with the mere passage of time. Auspiciously, reason prevailed.

I can scarcely comment whether it was GADGET that shaped me or if I was already shaped to appreciate it – certainly both hypothesis coexist in truth. From the very first instant, no single aspect about it seemed hospitable or uncomplicated. All the while, it would serve me just the right amount of ambiguity and opacity that I hoped it would. Such was my fondness of it that I went to indescribable lengths to establish contact with its maker, whom I persuaded into giving me an interview for my now defunct website.

Perusing the pages of INSIDE OUT WITH GADGET but a moment ago, the visual narrative of these obsessively well-rendered contraptions, dramatis personae and geography tells of an unparalleled concept that has but gained with age.

III.

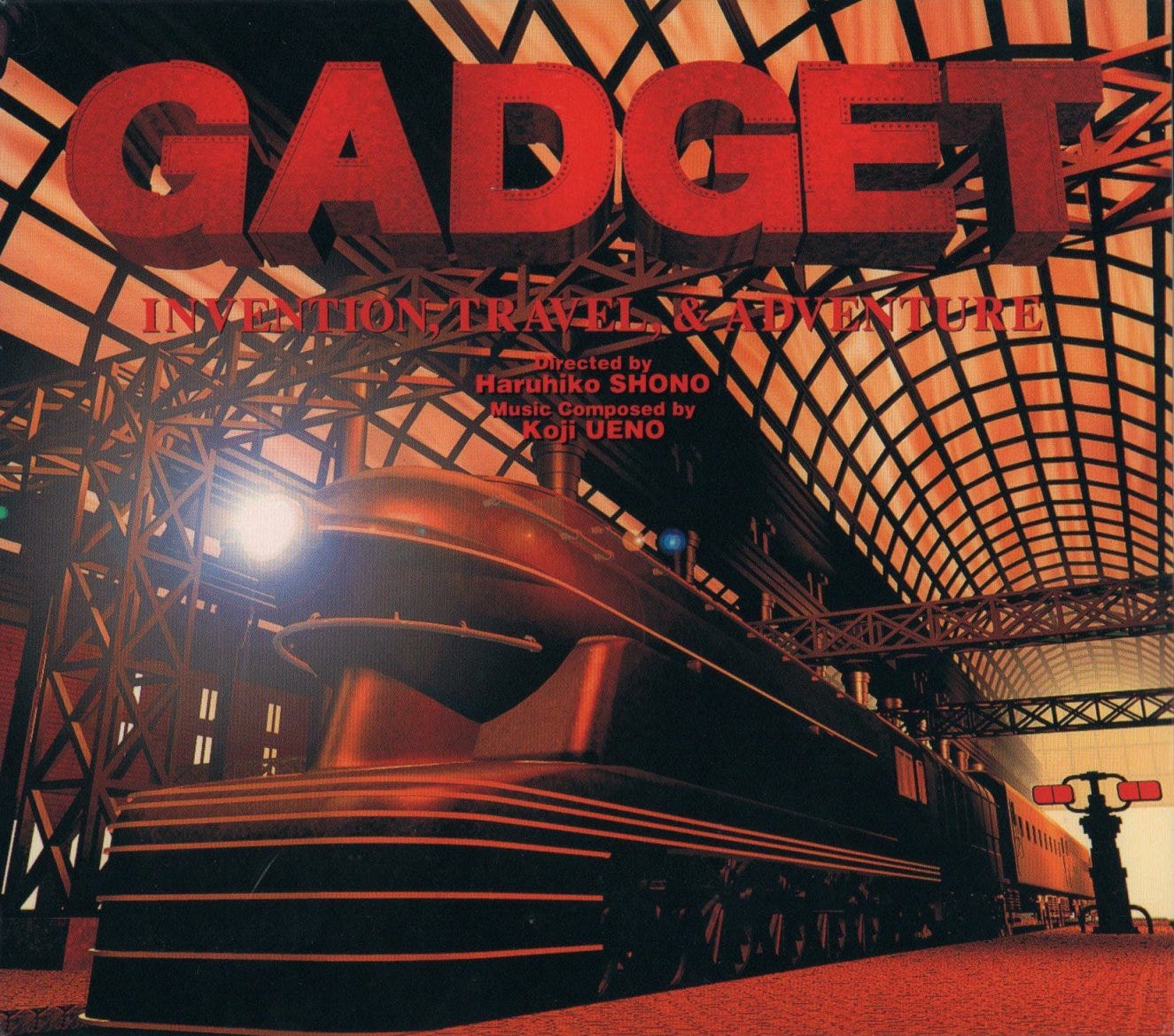

Shenmue

Yu Suzuki

SEGA AM2/Ys Net, 1999

It is no bold claim that SHENMUE is the single most ambitious video game ever created. This is largely unrelated with its famed multi-million dollar budget or its drawn-out development cycle spanning across two console generations; rather, it stems from the insurmountable magnitude of its aspirations and foresight.

It was on the basis of hard-earned credence that Yu Suzuki, himself responsible for a sizeable share of SEGA's proceeds over the decades, was able to persuade finance directors and creditors alike that his next undertaking was to revolutionise the medium and, in doing so, thrust the corporation to the crest. On the first account he did not err; on the latter, he may well have overestimated the capacity of turn of the century audiences to embrace the game's distinct brand of novelty.

And yet it is not for its scale and grandeur that I so dotingly remember this epic poem on mundanity, this quintessentially eastern "bildungsspiel". The finer details contained within it were the element that kept it apart from the rest for long, moving as we were into a decade morbidly obsessed with the hollow pledge of bigger-and-better. Most videogames lacked - lack - an identity. Of this ailment, SHENMUE did not suffer.

All about it felt hand-woven with diligence and purpose. Most every object in sight, however common, could proudly take up the entirety of the screen for perusal and admiration. Locations, interior or exterior, teemed with atmosphere and sense of place. Every denizen is scrupulously designed to bear the likeness of an individual. Its maddening degree of veiled minutiae was the reward for all players inquisitive - those for whom the compelled periods of waiting felt strangely appropriate.

In this regard, me and my brothers were the most dutiful and accomplished players of this game: forever open-mouthed at what could be interacted with, eager to descend into its depths by candlelight, celebrating each passage into the evening at the sound of dog barks from afar, feeling peckish at the sound of frying noodles in a polygon-rich restaurant, mimicking the elderly practicing Tai Chi in the park, and all the while being shaped by its wisdom and awed by its oubranching charms.

IV.

Silent Hill

Keiichiro Toyama

Konami (KCET), 1999

SILENT HILL was the culmination of a decade of remarkable horror-themed video games. A true original, it succeeded in drawing its inspiration from a judicious selection of sources largely untapped by the industry until then, heralding a new and provocative paradigm few were able to do right by.

As an adolescent hardened by a myriad of the vilest M rated films public television and a small town video rental club could supply, I fastidiously avoided playing it after certain hours of the evening, when reason and clarity begun to peter out, and more irrational predispositions prevailed.

The grotesque spectacle therein exhibited was carefully orchestrated to leave a lingering impression by sustaining the player at elevated degrees of tension and disorientation, and to needle one’s nerves with the sharpest punctures. Toyama’s approach to design emphasized visuals and sounds in equivalence. The careful positioning light sources, camera angles and its hopeless palette were regularly bested by a malicious collectanea of siren wails, startling radio noises, critter screeches, and those inexplicable thuds, hums and clatters that aimed to reciprocate and play a game of their own with one’s mind. And, as if this did not suffice, there was an Akira Yamaoka soundtrack.

Yet its most disruptive element rested in its novel concept and heap of clever references; so bountiful, in effect, that they lent subsequent developers a wealth of material to draw on, adapt, rework and, lamentably, squander. The game dispensed with the habitual and predictable scenarios that so defined the nineties and found its position closer to folk horror themes and symbolism, devoutly Lynchian, establishing a its traumatizing fabrications from a common, contemporary and conceivably relatable premise. This was even truer for the sequel which transcended the original.

V.

Rez

Tetsuya Mizuguchi

United Game Artists, 2001

Not much was known – could be known - about REZ at the time of its release. Despite the upsurge of video game websites , critics by and large failed to grasp the object at hand, betrayed by the paucity of their vocabulary and fanatical pigeonholing in their many bids to describe it. On the other hand, what erratic butterfly, the game did not lend itself to effortless capture.

I greeted it with all but insincere reactions: the few first minutes of the hour with much frowning of the eyebrows; the remainder with a markedly dropped jaw. I was bemused by the unconflicting amalgam of novelty and familiarity. The procession of enemies was tantalizing, like PANZER DRAGOON on dimethyltryptamine; the sultry, pulsating beats rivalled those of a WIPEOUT; added to the exhilaration of logging into a cyberspace so evocative of TRON’s.

REZ was daringly experimental at a time when the maturing audiences begun to surrender the gamepad to take on other pursuits. With its newly-formed software house UGA, Mizuguchi was presciently aware of this phenomenon and sought to integrate the intricacy of his experiences outside the game industry – from club music to contemporary art exhibits - in all his ensuing creations.

That which REZ possesses that is thoroughly original and unseen continues to transcend description. Like a visit to an ancient oracle, it whispers a unique divination to each inquirer. In particular, its aptly-named “Trance Mission” was confounding, frenzied and an unsettling insight of the unexploited potential the medium had yet to offer.

The recent release of REZ ∞ - one from the handful of game reeditions I can vouch for - vindicated that which has long been my unchanging contention. I delight myself in the thought that someone just as young as I was then can now derive similar pleasure from its discovery, as if the fifteen years in between amounted to nought.

VI.

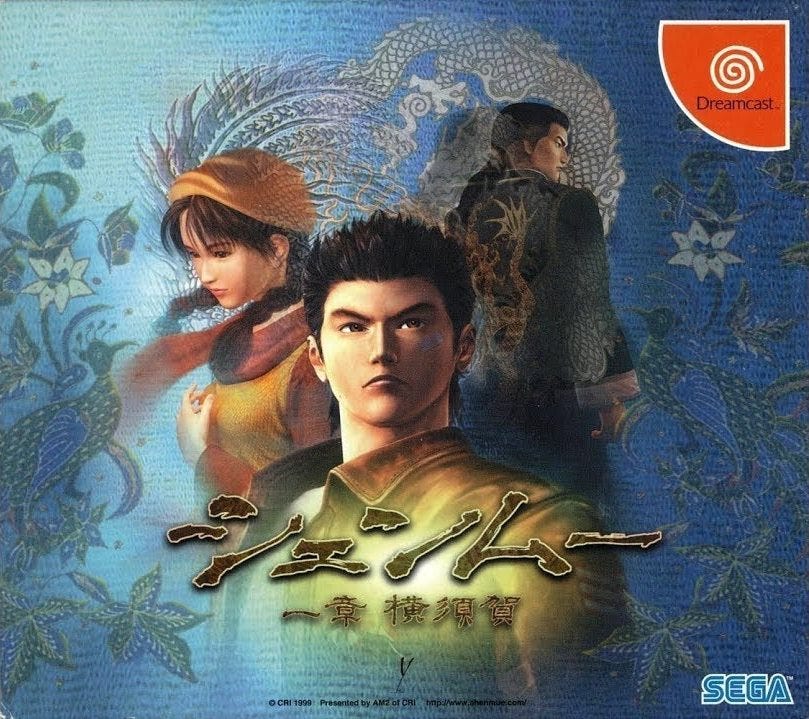

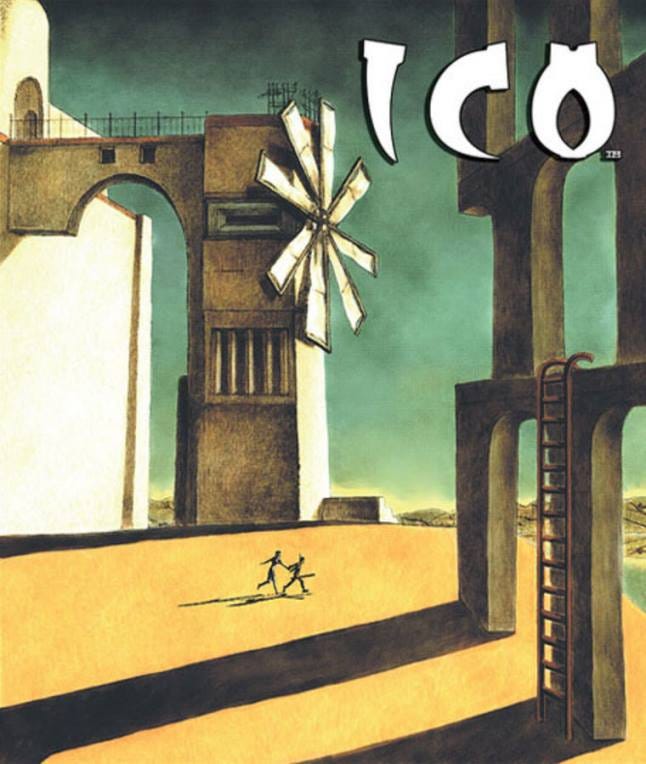

ICO

Fumito Ueda

Team ICO/SCEJ, 2001

Life’s circumstances would attenuate my once intense fervour for video games. Having moved into a different city to continue my studies, other seemingly irreconcilable pursuits rapidly took precedence, now finding myself surrounded by a society for whom new media was the sporadic object of sneering and jeering. They had some of it right.

The Playstation 2 had just been released, to much roar and delight, the entire industry was undergoing its largest boom and there I was in my student’s quarter, translating poetry with my propelling pencil; or beholding the lit ashes of my pipe in the dark, keeping only Bartók spinning on my stereo for company.

Periodically, I would take the opportunity to probe the market for what was novel, sifting through imported specialty magazines or glancing the shelves every other week. It was on one such occasion that this bewildering cover came into view, instantly piquing my curiosity. Whoever had created this game was in the know.

And no words ever did it justice. It is the purest game design in (recent) history, a totem to be revered at the altar of the medium. A phenomenon in aesthetics, all things mechanical meticulously fitted together. A torchbearer in minimalism. A revelation of the utmost ambiguity, second only in complexity to its own kin.

It was the one title that game designers I have contacted over the years spoke about with unbridled enthusiasm – all save one, Kenji Eno, who failed to summon up the words.

ICO denotes new beginnings. To some it represented true north on their creative compass, coming into the trade for their first time; to others the object of reinvigoration, altering the course of their careers even if in the smallest of ways. For me the same, in that it reconciled my newfound interests with that childhood plaything I was only too ready to store in my mind’s attic. For that, I shall forever remain indebted to Fumito Ueda.

To be continued…